How Rates Move/Rate Lock

Why Mortgage Rates Move

Unlike most other interest rates, those for mortgages (except ones for existing adjustable-rate mortgages) are largely determined by the supply of money into the market from investors and the demand for such loans from consumers. That supply is heavily affected by the amount of risk investors are prepared to sustain in their portfolios. When spooked by economic uncertainty, they tend to buy safer assets, including mortgage securities, which can result in an increased supply of product (cash) that drives down the price (rates). When they’re more confident, they tend to invest in riskier but more profitable assets, which reduces the supply of money for home loans, and pushes up rates. A second influence is perceptions of how inflation rates are likely to move over the long term, but that usually tends to be a less important factor in daily and short-term movements. None of this is to suggest the Federal Reserve doesn’t affect mortgage rates, merely that it does so only indirectly by influencing investor sentiment.

The relationship between 10-year Treasury bonds and mortgage rates is more complicated. Investors generally view those bonds and mortgage securities as similarly secure havens for their money when they’re spooked – with bonds the safer of the two. That means they tend to buy or sell both at the same time, depending on their level of confidence in the U.S. and global economies. So many lenders refer to those particular Treasury yields when setting their rates. Usually, the relationship between 10-year Treasury yields and mortgage rates is surprisingly close, though rates tend to be less volatile, and sometimes the two drift apart a little.

Interest rates and bond prices generally move in inverse directions.

When market interest rates rise, prices of fixed-rate bonds fall, aka interest rate risk. But why?

When you buy a bond or fund a mortgage, you’re lending money to the bond’s issuer, or borrower, who promises to pay you back the principal on the bond’s maturity date. Like a mortgage! Before the bond is due, the issuer also promises to pay you periodic interest payments to compensate you for the use of your money based on the stated interest or coupon rate, which is generally fixed at issuance.

The answer to why the inverse relationship exists lies in the concept of opportunity cost. Investors constantly compare the returns on their current investments to what they could get elsewhere in the market. Market interest rates are changing constantly. The fixed interest rate on a bond becomes more or less attractive to investors based on its relation to market rates. For example, a $1,000 new issue of bonds, or a mortgage, carrying a 5% coupon pays you $50 a year in interest.

Now let’s suppose that later that year, interest rates go up and new $1,000 bonds, or mortgages, are paying a 6% coupon, or $60 a year in interest. Who is going to pay the $1,000 face value for your 5% bond seeing as they can get 6% elsewhere? Why would I, or some money manager in Tokyo, want to only earn 5% instead of 6%? So, in order to sell, you’d have to offer your bond at a lower price, a “discount,” that would enable it to generate approximately 6% to the new owner. In this case, that would mean a price of about $833.

Similarly, if rates dropped to below your original coupon rate of 5%, your bond would be worth more than $1,000. It would be priced at a premium, since it would be carrying a higher interest rate than what was currently available on the market.

Obviously, many other factors go into determining the attractiveness of a particular bond, or a mortgage: the length of time until the bond matures or loan pays off, whether or not its interest is taxable, the creditworthiness of its issuer or the borrower, the likelihood that the issuer or borrower will pay off debt early, and so on. But the important thing to remember is that change occurs in market interest rates virtually every day. The movement of bond prices and bond yields is simply a reaction to that change.

How the Fed Impacts Mortgage Rates

From RobChrisman.com:

With the Fed decisions to raise or lower rates, we’re commonly asked how the Fed moves impact mortgage rates. MCT offers an excellent primer that reminds us, “Many people believe the Federal Reserve, through the actions of the Federal Open Market Committee, has a direct impact on mortgage rates. It’s actually more so that speeches from Federal Reserve Committee members, announcements of what the Fed is doing, and its actions in the open market serve as useful predictors of future rate movement.

“Changes in the federal funds rate trigger a chain of events that affect other short-term interest rates, foreign exchange rates, long-term interest rates, the amount of money and credit, and a range of economic variables (e.g. employment, output, and the prices of goods and services). The fed funds rate affects short-term loans, such as credit card debt and adjustable-rate mortgages. Long-term rates for fixed-rate mortgages are generally not affected by changes in the federal funds rate but track the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield much more closely.”

Dennis C. Smith of Stratis Financial opines, “The Federal Reserve’s stated purpose is, “Conducting the nation’s monetary policy by influencing money and credit conditions in the economy in pursuit off full employment and stable prices. The Fed has several tools available to increase or decrease the amount of money in the economy. Full employment results in greater demand for goods and services, which puts upward pressure on prices, i.e. inflation. Less than full employment decreases overall purchasing power and ability. Lower demand leads to stable, or declining prices.

“Contrary to what many believe, the Federal Reserve only controls one interest rate, the federal funds rate (referred to often as the “benchmark rate”). This is the rate that banks lend money to each other, typically on an overnight basis. Mortgage rates are determined by investors who purchase mortgages as an investment. The mortgage market is generically known as MBS, or mortgage-backed-securities. Investors want to make a profit, their decisions to purchase or not purchase any investment is based upon their opinion as to what they think will happen in the future and if their investment will be worth more or less money. In the case of MBS, this includes what they feel interest rates will be, or should be, in the future. Part of their decision-making criteria is what they feel the Fed will do in regard to monetary policy, or what the Fed has announced it will do.”

How will I know if mortgage rates are going up or down?

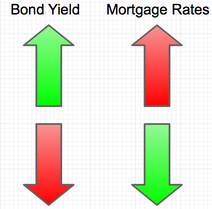

Typically, when bond rates (also known as the bond yield) go up, interest rates go up as well. And vice versa. Don’t confuse this with bond prices, which have an inverse relationship with interest rates.

Investors turn to bonds as a safe investment when the economic outlook is poor. When purchases of bonds increase, the associated yield falls, and so do mortgage rates. But when the economy is expected to do well, investors jump into stocks, forcing bond prices lower and pushing the yield (and mortgage rates) higher.

– 10-year bond yield up, mortgage rates up.

– 10-year bond yield down, mortgage rates down.

So a good way to predict which way mortgage rates are headed is to look at the 10-year bond yield. You can find it on finance websites alongside other stock tickers, or in the newspaper. If it’s moving higher, mortgage rates probably are too. If it’s dropping, mortgage rates may be improving as well.

Conventional (Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac and Non-Agency investors) and Government (FHA and VA) lenders set their rates based on the pricing of Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) which are traded in real time, all day in the bond market. This means rates or loan fees (mortgage pricing) moves throughout the day, being affected by a variety of economic or political events. When MBS pricing goes up, mortgage rates or pricing generally goes down. When they fall, mortgage pricing goes up. Tracking these securities real-time is critical. For more information about the rate market, contact us directly. We are among few mortgage companies who have access to live trading screens during market hours, in addition to pricing software that compares the top wholesale lenders in the market for pricing competition and comparison.

Q&A Regarding Rate Locks

What is a rate lock?

A rate lock is a guarantee from a mortgage lender that they will give a mortgage loan applicant a certain interest rate, at a certain price, for a specific time period. The price for a mortgage loan is typically expressed as “points” paid to obtain a specific interest rate. Your VMG Loan Consultant will show you several rates equating to optional buy-down or buy-up (lender credits) to determine what pricing is most favorable for your situation.

When do I lock an interest rate?

You’re in a position to lock in an interest rate when your application is received, loan approved, and purchase contract executed (or if a refinance immediately following application).

How much does a rate lock cost and what if my lock expires?

VMG does not charge any application or initial rate lock fees. If the rate lock is going to expire, your Loan Consultant will discuss the extension or re-lock options with you which may impact lender credits (if applicable) or net costs vs. original lock terms. Each investor holds a specific lock policy and calculation for any costs associated with lock extensions or re-locks.

What is a mortgage rate lock float down/renegotiation?

A mortgage rate lock with the option to reduce the locked interest rate if market interest rates fall during the lock period. A rate lock with a float-down option can provide the borrower with security against an increase during the rate lock period, while the float-down option allows the borrower to take advantage of a fall in interest rates during the lock period. Due to the large number of investors VMG works with, each carry a unique rate lock renegotiation policy. The option will only be exercised by the mortgagor after an internal adjustment to price and if available as a benefit to the borrower. VMG always monitors pipeline for any opportunities.